TLDR

Findings

- We find greater separability with Jaccard distance on spline codes vs L2 and cosine similarity on concatenated model activations.

- Grokking produces highly separable spline clusters but non-grokked models also exhibit the same separability with spline codes vs activations. This allows us to find 11 clusters on MNIST for grokked models (10 classes + 1 uncertain cluster) and 10 clusters for non-grokked models (10 classes).

- Grokking is hard to induce and we should not expect concepts to be grokked. However, positive results in the non-grokked example warrants future investigation

Next: I aim to build supervised classifiers using spline codes to identify different concepts and behaviors like grammatical categories (e.g. part of speech), in-context references, and high-level categories (e.g. sports vs not sports) to determine whether separability remains advantageous vs current methods (probes).

Objectives

This week, I wanted to:

- Provide baselines for the main use case of spline clustering: unsupervised feature finding

- Determine the conditions for when spline clustering works/fails - in particular, if SC depends on training depth (weakly trained → grokking)

Literature entry: A-SAEs and Splines

Spline codes turn continuous firing intervals into binary states, effectively reducing the magnitude distance caused by active neurons. This runs opposite to the intuition that activation intervals correspond to different concepts. (Fel et al., 2025; Lin, 2023)

However, I contend that this intuition merely originates from operations in residual space (MLP neurons).

Hypothesis: Representations in the residual stream (intermediary vectors) are probably compressed aggregations. Operations by MLP blocks, which first decompress the input matrix, could be basis-aligned such that decomposing them would yield features.

Recent success with Archetypal SAEs (A-SAE) may support this hypothesis (Fel, Lubana, et al., 2025; Fel, Wang, et al., 2025).

Figure 1: Archetypal SAE architecture: is constructed using the Archetypal Dictionary.

A-SAEs create a dictionary of latents that attend to the non-negative components of model activations. To achieve this, ReLU is applied to the dictionary entries and their row-wise sum is constrained to equal 1.

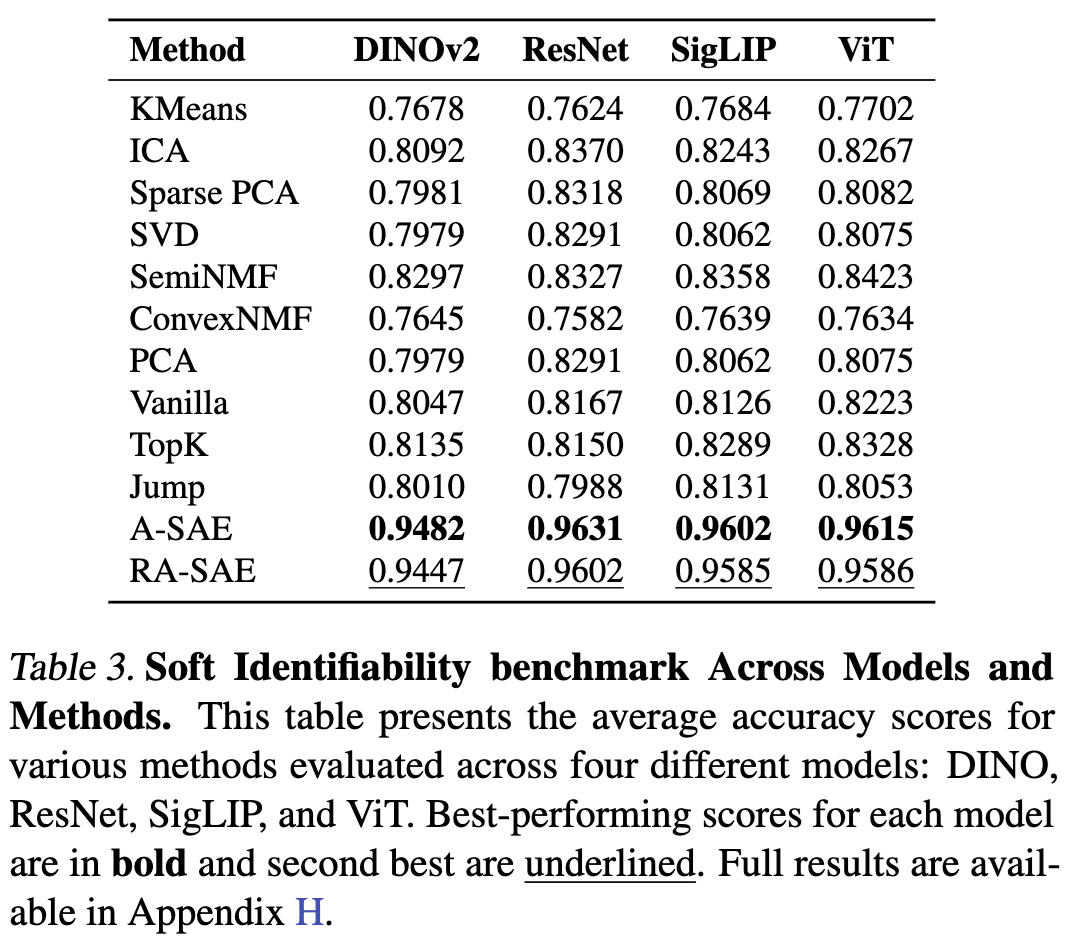

This approach outperforms activation clustering and baseline SAE approaches:

Hypothesis: I posit that obtaining the binary states () of the model’s intermediate ReLUs is equivalent to the weighted sum clustering operation performed by A-SAEs on model activations ().

Intermediate activations are aggregations of ReLU outputs. A-SAEs account for this by reverse-engineering coefficients for each such that a combination of coefficients are associated with a given feature.

However, if we could associate -dimension binary states to each sample (instead of activations), we can simply cluster neuron state vectors to obtain features without reconstruction. For example, if for some layer, the output is:

The spline code corresponding to this would be:

If this holds true, we should be able to:

- Cluster binary ReLU states and find interpretable features

- Provide guarantees for the formation of distinct regions spanned by ReLU states

- Current literature points to grokking as the driver of region formation.

- However, not all models grok - do we find that models still form regions without grokking?

To validate this, I performed 3 experiments:

- Experiment #1: Demonstrate that spline code clustering outperforms current metrics for latent comparison

- Baseline: vector similarity, L2 on model activations

- Experiment #2: Perform clustering on spline codes vs model activations; find usable insights from spline code clustering

- Baseline: Can we derive the same insights from model activation clustering?

- Experiment #3: On non-grokked models: spline code clustering vs activation clustering

- Question: Do well-trained enough models exhibit region formation despite not grokking?

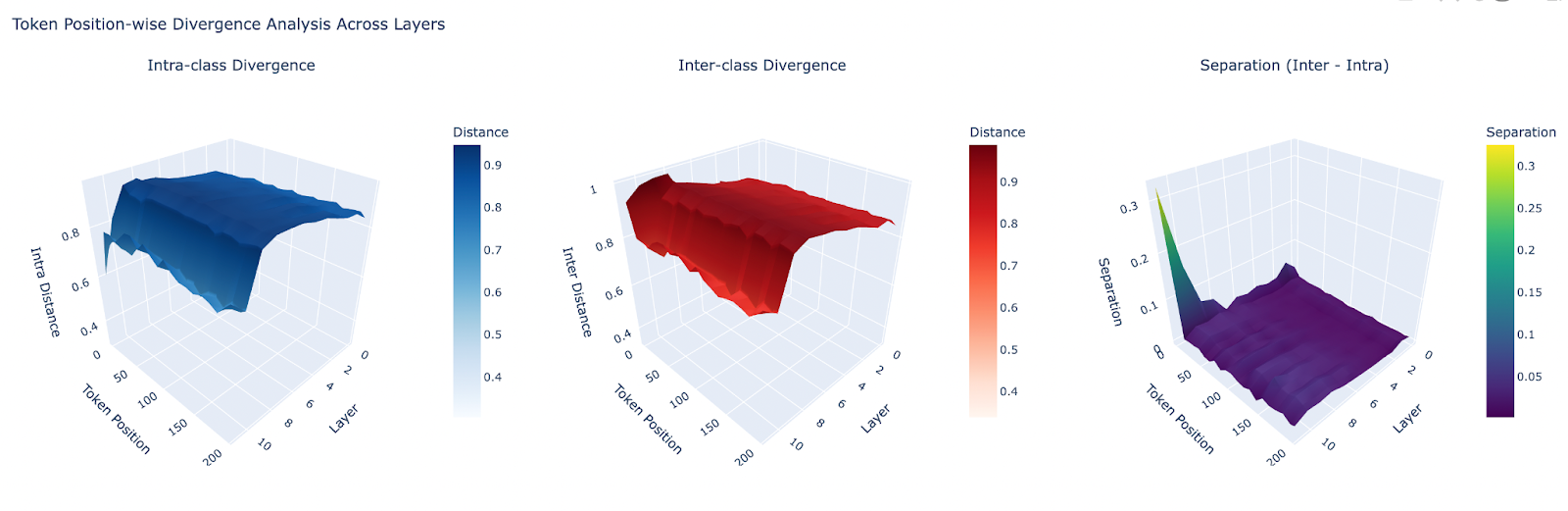

Spline code vs activation space distances

Experiment #1: Are spline codes uniquely separable vs model activations for the grokked MNIST model?

Result: Yes, it seems that inter-class distances between spline-encoded samples are more separable than model activation-encoded samples.

We measure distances for two categories:

- Intra-class - between samples of the same digit

- Inter-class - between samples of different digits

The MNIST model was trained with the ReLU gate - hence, we obtain spline codes by filtering for when and stack codes from each layer in order:

for each spline code corresponding to a single layer’s neuron binary firing pattern.

We collect model activations in a similar way, collecting nn.Linear outputs and stacking them layer-wise. We then take the following distance metrics:

| Spline Code | Model Activations |

|---|---|

| Hamming distance | L2 |

| Jaccard distance | Cosine similarity |

We find greater separability by spline code distances vs model activation distances:

Figure 2. Spline code metrics: Hamming and Jaccard distances for 3000 MNIST samples from the train set.

In contrast, distances in activation space overlap greatly:

Figure 3. Model activation metrics: L2 and cosine distances for 3000 MNIST samples from the train set.

Note: Cosine distance is taken as .

The separability we see above is an indicator that clustering by spline codes could be more efficient and performant than clustering model activations.

Clustering via spline codes vs model activations

We implement the following clustering algorithms and measure their performance by taking their Silhouette score, Calinski–Harabasz index and Davies–Bouldin index.

| Clustering Algorithms |

|---|

| K-Means |

| DBSCAN |

| Ward’s Method |

| Unweighted Average Linkage (Hierarchical) |

Grokked MNIST Model

Experiment #2: Perform clustering on spline codes vs model activations; find usable insights from spline code clustering

Result: Spline codes produce more pronounced clusters using K-Means, aligning with output classes for an MNIST trained NN. For a grokked NN, we find 11 classes corresponding to each of the 10 digits and a class for uncertain classifications.

Baseline: Model Activations

We take activations at the nn.Linear layers of the MNIST model and stack them to form a comparable large vector that captures model operations for the given sample.

It appears that clustering based on this aggregated activations vector yields subpar results.

The most performant clustering method across all metrics, K-Means, finds only ~8 clusters which do not correspond to the MNIST classes.

When parametrized to find k=10 clusters, similar digits (e.g. 4, 7 and 9) are pushed into the same category, indicating overlapping representations (in linear point distances).

Even worse clustering scores can be observed when taking only the middle layer’s and only the last layer’s activations.

Spline Codes

In contrast, taking the stacked spline codes from each layer and clustering samples based on this, we find 11 clusters using K-Means, corresponding closely to the 10 MNIST classes and a cluster for high uncertainty samples.

Visualizing the samples in 2D by reducing their spline code with PCA, we find cleanly separated clusters which mostly correspond to their predicted classes.

At k=10, each digit is allocated to a given cluster, except for digits 2 and 5 which are both attributed to Cluster 2. The resulting spare cluster, Cluster 7, is allocated to the ‘uncertain’ class as visualized above.

The graphs above indicate the utility of spline code clustering for the MNIST grokked model. However, models can still be performant without grokking during the training phase.

We need to understand if this finding translates to trained models that exhibit high performance without grokking.

Non-Grokked Model

Experiment #3: On non-grokked models: spline code clustering vs activation clustering

Result: We observe low performance when clustering model activations, equivalent to clustering activations for the grokked model. Similarly, we obtain lower separability scores for spline code clustering but still find meaningful clusters forming with respect to the MNIST classes.

Spline Codes

A new MNIST model was trained on the MNIST train set with the same width and depth as the grokked model, but only for 20 epochs (vs 10,000 epochs with grokking). The model achieves train accuracy of 99.57% and test accuracy of 97.97%.

For spline code clustering, we find lower silhouette and CHI scores denoting less separable categories. Our prior aligns with this as we expect the model trained on less epochs would not find the most optimal classification parameters such that its internal representations are partitioned cleanly.

Using the elbow method with K-Means, we determine an optimal k=10 clusters. Looking at the PCA chart, we see distinct regions corresponding to the digit classes but no distinct clumps to the degree exhibited by the grokked model’s PCA plot.

Notably, however, each of the clusters line up perfectly with the digit classes. This suggests that locally stable regions might have already formed at this stage and that, in contrast, grokking may exhibit two unique traits:

- ‘tighter’ regions corresponding to learned concepts

- such that interpolating between two clusters move out-of-distribution

- an internal representation for uncertainty that exists as a separate region entirely

- e.g. Cluster 8 in the Grokked PCA Plot

Baseline: Model activations

In contrast, clustering model activations again produces noisy results:

Baselining expectations

Below are reasons not to be excited by spline code clustering, especially in non-grokked models:

1. Intra-class vs inter-class spline code distances are less pronounced for non-grokked models.

Grokked model inter- vs intra-class distances exhibit a large gap in between the two distributions. The non-grokked model’s distances are still bimodal but overlap:

This indicates that taking the spline code difference may not be advantageous over cosine / L2 distance for undertrained models:

2. Inducing grokking during the training phase requires hyper-parametrization.

Without optimal learning rate and dropout parameters, a model will not grok on training data despite all else being equal.

Figure: An MNIST model trained to 1,000 epochs neither groks nor produces separable spline code representations to the degree earlier shown.

This is an especially difficult constraint for large language models which are not trained on explicitly defined categories.

Final Word

Despite these constraints, the following findings warrant future investigation:

Spline code clustering still outperforms model activation clustering for non-grokked models

(as shown in Non-Grokked Model)

Figure: K-Means clustering at k=10 for spline codes (top) and activations (bottom).

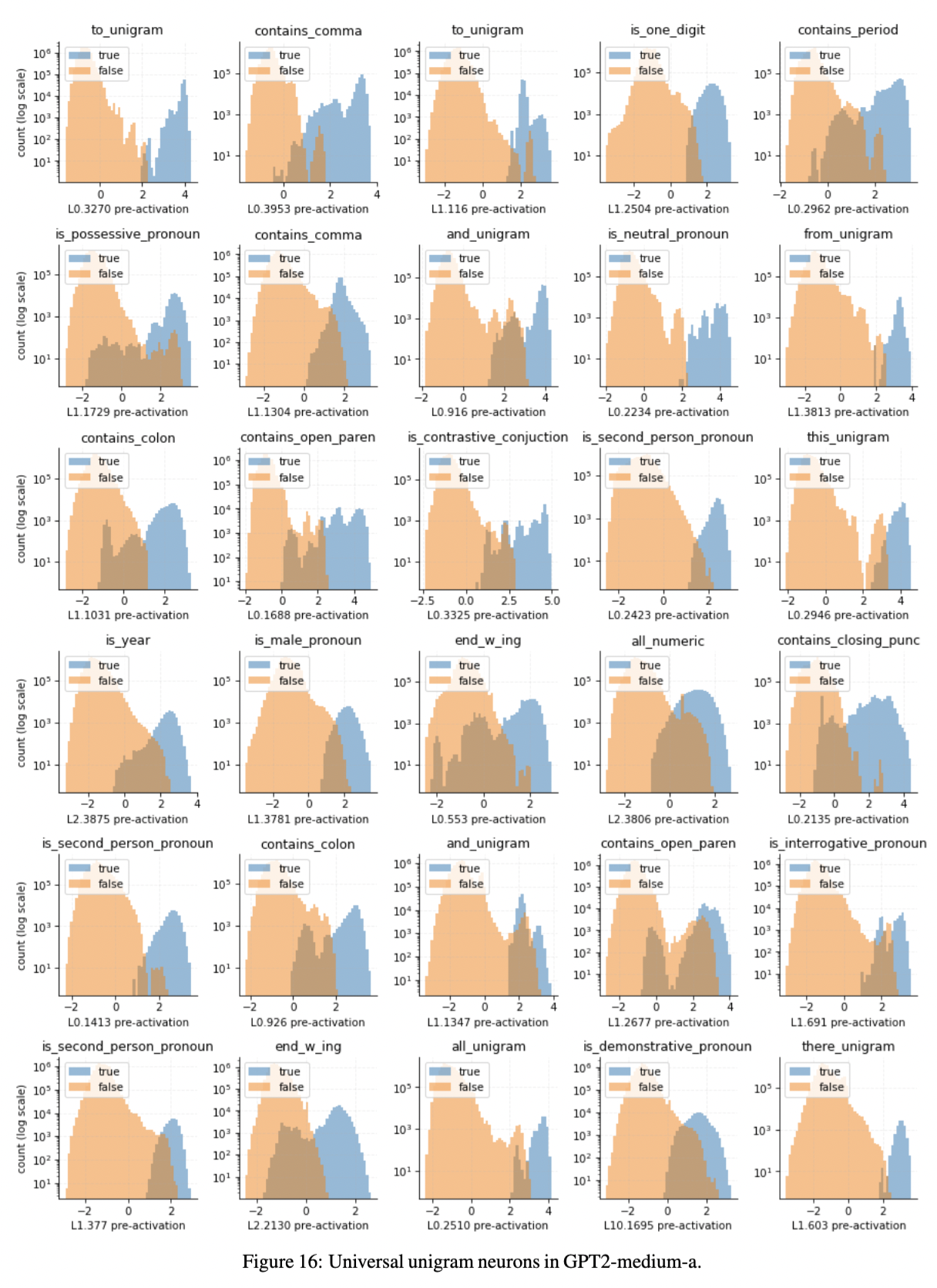

Pre-activation neuron patterns exhibit multimodal distributions over semantic features

Gurnee et al. (2024) investigated the pre-activation patterns of universal MLP neurons - neurons consistently present despite training with different seeds.

Their pre-activations exhibit bimodal distributions corresponding to the presence or absence of the attributed feature.

Strikingly, the transition between true and false categories don’t always occur at x=0, the critical point of the gating function. The point , for which the function is nearly linear at, appears to be a critical point as well.

Furthermore, for some features (e.g. contains_open_paren), both true and false distributions appear bimodal. This suggests that the neuron might mediate 2 or more co-occurring sub-features (e.g. open parentheses binding text vs closed parenthesis binding digits).

The observed distribution is consistent with the hypothesis, hinting that it may be groups of intermediary MLP neurons that encode features.

The low number (5%) of universal neurons may also hint at the fact that interpreting continuous model activations may not find meaningful concepts. Instead, the distributions must be binarized into active/inactive states.

Conclusion

The findings above illustrate some advantages with using spline codes, which capture information across all layers, for unsupervised target detection.

Previous experiments showed that a bijective ViT’s MLP components behave similarly, albeit with spline codes only being utilized fully in the special token [CLS] position for an ImageNet classification task.

Next Steps

Future experiments should establish whether the same pattern, of spline codes being more easily separable, applies to language models trained without explicit target variables for which to form representations.

My prior is that the transformer’s task of modeling language as being agglomerative vs discriminative, tending to merge concepts rather than split them apart cleanly. It remains to be seen if this is truly the case.

I aim to build supervised classifiers using spline codes to identify different concepts and behaviors like grammatical categories (e.g. part of speech), in-context references, and high-level categories (e.g. sports vs not sports) to determine whether separability remains advantageous vs current methods (probes).

To accomplish this for an autoregressive model, I’ll start with detector features which we expect to align with the current token position (e.g. is_verb spanning a column vector) and scope out spline behavior for higher-level features (e.g. is_narrating, etc.*) that could exist across a range of embedding positions.

Implications:

- If we find that concepts are more easily separable with spline codes in LLMs, it’s more likely that unsupervised feature finding is possible.

- There would be more evidence to support the claim with gate switches.

* Note: I’m open to suggestions here as to what features are more important to find or more likely to exist!

Why not push the gate switching direction?

It seems that gate switching as a metric relies heavily on the assumption that two points belong to categories that themselves are embedded in distinct regions as expressed by their spline code. The assumption has not been sufficiently proven hence it may be imprudent to run bulk experiments to test the empirical finding with gate switching.

Furthermore, gate switching is highly dependent on linear interpolation. There is no consensus that linear interpolation is the “proper” traversal in activation space.

- Fel, Wang, et al. (2025) suggest that linear interpolation travels outside of the model’s manifold and hence would travel to points that are out of distribution.

- Gurnee et al. (2025) find line-length features spanned by manifolds created by select attention heads.

I’d like to start from the idea that a set of samples that contain a feature might share a subset of spline codes and build out from there.

References

Fel, T., Lubana, E. S., Prince, J. S., Kowal, M., Boutin, V., Papadimitriou, I., Wang, B., Wattenberg, M., Ba, D., & Konkle, T. (2025). Archetypal SAE: Adaptive and Stable Dictionary Learning for Concept Extraction in Large Vision Models (No. arXiv:2502.12892). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.12892

Fel, T., Wang, B., Lepori, M. A., Kowal, M., Lee, A., Balestriero, R., Joseph, S., Lubana, E. S., Konkle, T., Ba, D., & Wattenberg, M. (2025). Into the Rabbit Hull: From Task-Relevant Concepts in DINO to Minkowski Geometry (No. arXiv:2510.08638). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2510.08638

Gurnee, W., Ameisen, E., Kauvar, I., Tarng, J., Pearce, A., Olah, C., & Batson, J. (2025, October 21). When Models Manipulate Manifolds: The Geometry of a Counting Task. https://transformer-circuits.pub/2025/linebreaks/index.html

Gurnee, W., Horsley, T., Guo, Z. C., Kheirkhah, T. R., Sun, Q., Hathaway, W., Nanda, N., & Bertsimas, D. (2024). Universal Neurons in GPT2 Language Models (No. arXiv:2401.12181). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.12181

Lin, J. (2023). Neuronpedia: Interactive reference and tooling for analyzing neural networks. https://www.neuronpedia.org